Wealth and Human Rights in a Capitalist World Part One: The Rubber Terror in the Congo

On one October afternoon in Belfast, Ireland, John Dunlop watched his nine-year-old son peddle away furiously down the road on his tricycle. Though they were an improvement over wooden and iron wheels, the solid rubber tires rattled the boy’s bones and caused him to bounce up and down on his seat like a jackhammer. John couldn’t take it anymore. He removed his son from the tricycle, dismantled it, and then began making his own wheels.

He molded some sheet rubber into the shape of a tube, and then inserted a one-way valve to fill it up with air. He then bent the valve and tied it off like a balloon. Wrapping it in Irish linen, he fastened it with nails to a large wooden disc. Finally, as a test, he rolled the old solid rubber tire alongside his new inflated invention across the backyard, and watched the results with bewilderment. The first wheel rolled for a short distance then fell over lamely, while his inflated wheel shot past, hit the back fence and bounded back.

It was revolutionary.

Dunlop invented the first commercially available, pneumatic rubber tire. He patented it in 1888, and the next year his friend, Willie Hume, installed the innovation on his bicycle and used it to easily win all four cycling events at Queens College Sports in Belfast, and subsequently won all but one in Liverpool, fascinating everyone and propelling the tire onto the market. Harvey Du Cros, one of the cyclists who lost to Hume in a race, approached Dunlop and together they created the Dunlop Rubber Company in 1890.

Unbeknownst to Hume, Du Cros, or Dunlop, however, was the Pandora's Box the trio had inadvertently ripped open. One man’s innocent attempt to create a smoother tricycle ride for his son would spur the massacre and exploitation of millions of people across the world over the coming years. And nobody could stop it.

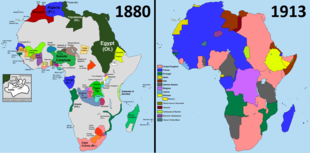

But first, let’s take a step back for some context. At this moment in history, the world had just entered an epoch the horrors of which it was only beginning to glimpse. This period, stretching from 1880 through 1913, is most commonly known as the Scramble for Africa. From its start, European powers controlled only 10% of the African continent, mostly holding territory along the western coast. By the First World War, only Liberia and Ethiopia were left untouched.

Until that time, Africa was typically seen as a dark continent to outside observers who had never seen nor heard very much about it except through mythological stories and fantastic speculations. Curiosity was high, and newspaper readership devoured whatever embellished tales of adventure were brought back by the occasional explorer. But with the technological development of the 1880s, Europeans were able to penetrate further inland, and yank back the curtain of mystery surrounding Africa’s inner workings.

Explorers arrived on steamships armed with newly invented weaponry, such as the repeating rifle, which could fire 12 rounds before reloading, and the Maxim gun, which fired 600 rounds per minute. Diseases which previously wiped out most foreigners were combated with improved medicine, and a resurgence of Christian zealotry fueled colonial sentiments across the West.

Imperialism at this time, like most other state-backed gestures of ostensible altruism, was rationalized to those carrying it out and justified to those observing it with appeals to grand moral obligations. It was the “white man’s burden” to Christianize the heathens, civilize the savages and bestow upon the poor the blessings of free trade. The pompous motive was beautifully articulated by King Leopold II of Belgium when he said, “To open to civilization the only part of our globe which it has not yet penetrated, to pierce the darkness which hangs over entire peoples, is, I dare say, a crusade worthy of this century of progress.”

And it was Leopold himself who spearheaded the Scramble for Africa. During the early ‘80s, he sent expeditions to construct outposts at the mouth of the Congo River, and in 1884, after an extensive lobbying campaign, he partially persuaded and partially tricked the US secretary of state into recognizing his claim to the Congo. The next year, King Leopold officially founded the Congo Free State, and before the decade was over, other major powers like France and Germany followed suit with the US in recognizing the colony.

At the same time, the rest of Europe was “scrambling” for their own chunks of territory. The Berlin Conference was held in 1884, where the European powers famously gathered for several months to begin the process of dividing up Africa between themselves, drawing national borders that ran straight through indigenous communities. With economic depression at home and tension flaring over who would have political preeminence in Europe, they came together intending to prevent the chaotic flood of white men into the southern continent’s interior from sparking a war between competing imperial powers. At this meeting, which would determine the fate of Africa’s people, not a single African was present.

To head his colonial venture, Leopold hired Henry Morton Stanley, a renowned Welsh adventurer and adrenaline junkie who enthusiastically fought on both sides of the American Civil War, to lead his exploratory efforts in the Congo. “Be discreet,” Leopold told his minister in London. “I’m sure if I quite openly charged Stanley with the task of taking possession in my name of some part of Africa, the English will stop me. If I ask their advice, they’ll stop me just the same. So I think I’ll just give Stanley some job of exploration which would offend no one, and will give us the bases and headquarters which we can take over later on.” Above all, I do not want to risk losing a fine chance to secure for ourselves a slice of this magnificent African cake.”

The duplicity was necessary, as one of the conditions agreed upon both at the Berlin Conference and in the Americans’ diplomatic recognition of the Congo Free State, was the guarantee of free trade with the region. Leopold, on the other hand, had other plans.

For five years, Stanley’s crews of workmen carved a rough track around the Congo's rapids, cutting through brush and forest, filling in gullies and throwing log bridges over ravines. Teams of porters carried over 50 tons of supplies through the trail, and small steamboats were reassembled at the top of the rapids and traveled up river to land parties that established more bases on its banks. The station built at the top of the rapids was named Leopoldville, and the land above it was dubbed Leopold Hill.

Letters sent from Leopold to Stanley at this time illustrate the former’s insatiable hunger for land. “I take advantage of a safe opportunity to send you a few lines in my bad English,” he wrote. “It is indispensable you should purchase as much land as you will be able to obtain…If you let me know you are going to execute these instructions without delay I will send you more people and more material.”

Under the king’s orders, Stanley trekked up and down the river, signing treaties with hundreds of Congo basin chiefs, giving Leopold a trade monopoly over them. Typical examples were those signed by the chiefs of Ngombi and Mafela, who, in exchange for one piece of cloth per month, agreed to “give up to the said Association the sovereignty and all sovereign and governing rights to all their territories…and to assist by labor or otherwise, any works, improvements or expeditions which the said Association shall cause at any time to be carried out in any part of these territories…All roads and waterways running through this country, the right of collecting tolls on the same, and all game, fishing, mining and forest rights, are to be the absolute property of the said Association.”

Why, in not one case but over 400, would a village chief hand over all of his community’s land and his people’s autonomy for almost nothing in return? The simple answer is: he didn’t. Very few chiefs had ever seen the written word before, much less that of a foreign language. Furthermore, many clans and villages owned their land communally, even if some things were considered private property. While the concept of a treaty of friendship between two clans was familiar to them, the idea of signing one’s land away to a group of men from across the ocean was unthinkable.

The Belgians also borrowed some tricks from their European counterparts. The British and French colonists continually sold liquor to the Native Americans even though it damaged their communities, because the substance was addictive to those who bought it and profitable to those who sold it. Christopher Columbus frightened the indigenous people at Jamaica into trading with him by predicting the occurrence of a blood moon in 1504. Similarly, Henry Mortan Stanley “gifted” alcohol to the Congolese and persuaded them that he possessed magical powers to coerce and subjugate them.

In one example, he used a magnifying glass to light a cigar, claimed to wield the power of the sun, then threatened to burn down the chief’s entire village if he did not do what Stanley wanted. (This threat wasn’t always just a threat) In another case, Stanley loaded a gun while slyly hiding the bullet up his sleeve, then handed it to an African, ordering them to shoot him, and after they pulled the trigger, he bent down and pretended to retrieve the bullet from the ground, as if it had simply bounced off of his chest.

And of course, the Belgian colonists came right alongside Christian missionaries intent on proselytizing the black population with their religious scripture. It was all part of King Leopold's thinly-veiled good will, and he used the international religious support to finance the colony. At one point, the king even appealed directly to the Pope for assistance, asking the Catholic Church to buy his bonds, promising it would help spread Christianity across Africa. Desmond Tutu, a Nobel-Prize-winning South African rights activist, summed up the dynamic between newcomers and natives decades later. “When the missionaries came to Africa they had the Bible and we had the land. They said, ‘Let us pray.’ We closed our eyes. When we opened them we had the Bible and they had the land.”

For the Christians, colonizing the Congo was not merely a matter of converting the benighted natives. It was also a humanitarian crusade against Islam. The core message of Leopold’s PR campaign to muster support for his imperialism throughout the ‘80s was that someone needed to save the Africans from the terror of the Arab slave traders operating off of Zanzibar and the east coast. He stressed this imperative over and over again, banging the war drum so loudly that he was elected honorary president of the Aborigine’s Protection Society, a venerated British human rights organization.

So who was to be the magnanimous savior of the Congolese people? You guessed it. At an anti-slavery conference attended by representatives of the major European powers in Brussels in 1889, Leopold laid out his plans to combat the Muslim slave trade. He harped on the need for fortified posts, roads, railways and steamboats, all of which would support columns of troops pursuing the slavers. They also coincidentally mirrored the trade infrastructure he had been wishing to erect. To finance the plan, he requested permission from the conference to levy import duties on the Congo, effectively reneging on his promises to maintain free trade in the basin.

Toward the end of the 1880s, Stanley explored much of what hadn’t yet been mapped of the Congo. On one expedition, he led a column of men through the rainforest towards the border with Sudan, and treated them like animals. With minimal supplies, many of his men were near starvation, and when one tried to desert, he ordered him to be hanged. Anyone else who fell out of line was flogged.

The Congolese people were undoubtedly surprised when an exhausted, starving army of white men poured out of the brush and took their women and children hostage until they were supplied with food. Villages that refused to cooperate were simply burned to the ground. And on top of it all, Stanley still described his actions with moralistic rhetoric. The Maxim gun was “of valuable service in helping civilization to overcome barbarism,” he said.

One member of the expedition later wrote about his exploits. “It was most interesting, lying in the bush watching the natives quietly at their day’s work. Some women were making banana flour by pounding up dried bananas. Men we could see building huts and engaged in other work, boys and girls running about, singing. I opened the game by shooting one chap through the chest. He fell like a stone. Immediately a volley was poured into the village.” Another one of Stanley’s men packed the severed head of an African into a box of salt and shipped it to London to be stuffed and mounted by his Piccadilly taxidermist.

By 1890, there were 430 whites in the Congo, including soldiers, traders, missionaries and administrators. Compared to the 20 million people living in the territory, they were quite few in number, but not many state officials were needed. The vast majority of laborers were taken from the local population, and with advanced weaponry, several thousand men could effectively dominate the Africans, whose means of resistance was usually limited to bows and arrows, spears and the rare musket.

Slaves were bought for just three pounds to man the stations lining the river. The villages that sold its inhabitants to the white men peacefully were lucky. Others were immediately brutalized. There was no discernible pattern or principle to the violence; white officers shot Africans at their own whims, sometimes to kidnap their women as concubines, sometimes to intimidate the survivors into forced labor, and sometimes merely for sport.

The outwardly benevolent King Leopold, who had promised the world to open up the Congo to free trade and was renowned for his anti-slavery commitment, was now rampantly slaughtering and enslaving the Africans for his personal enrichment. By this time, he was aggressively shutting out foreign traders, and his claims of public service were nothing but lies; not a single school or hospital had been built. And yet, the veneer of beneficence continued to cloak what was happening inside the territory and allow those complicit in the atrocities to remain in denial. Congo state officials were paid a bonus for “reductions in recruiting expenses,” a euphemism for slavery, and slaves were referred to in letters as “volunteers.”

Leopold had the world fooled, but what he did not have were sufficient resources needed to exploit the entire territory. Instead, he carved portions of it into several giant blocks and leased their vacant land out as concessions to private companies. These concession companies had mostly Belgian shareholders and interlocking directorates that included many Congo state officials, and Leopold always made sure he held at least 50% of each company’s shares, allowing him to effectively attract outside capital while maintaining control and absorbing most of the profits. Structurally, he was like the manager of a venture capital syndicate today.

Even despite the clever setup, Leopold’s colony was proving to be a financial burden. Some money was made from the export of ivory and other goods, but by the early ‘90s, he had gone dangerously into debt. Luckily for Leopold, a veterinary surgeon in Belfast had discovered a way to improve his son’s tricycle ride.

John Dunlop relinquished ownership of his invention several years after patenting it, but with or without him, it took off like a horse from a barn. Three years after establishing its first tire plant in Dublin, the Dunlop Company built a second factory in Germany, then went on to manufacture in England, Australia, the US, Malaya and Japan. It became a hugely profitable multinational company that sold worldwide.

Throughout the 1890s, other firms dived in for a share of the market, such as Michelin & Cie, Goodyear and Firestone. The pneumatic rubber tire amazed consumers and sparked a bicycle craze that swept through Europe and across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States and Canada. People loved their new vehicles. The ride was comfortable, fun and convenient. Millions of bikes were purchased over the years, and an entire sub-culture formed around the product.

Of course, the rubber pouring into the first world had to come from somewhere. The Amazon was a hotspot for production, but the resource was also abundant in the equatorial rainforest of Africa, which reached through half of one particular territory: the Congo Free State.

Leopold suddenly found himself with massive amounts of an incredibly valuable commodity just sitting in his backyard. And with the added explosion of the automobile industry around the turn of the century, the global demand for rubber tires skyrocketed. From his palace in Belgium, the king watched in delight as his coffers filled with cash.

In 1897, the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber and Exploration Company spent 1.35 francs per kilo to harvest rubber in the Congo and ship it to the company’s headquarters at Antwerp, where it sold for prices that sometimes reached 10 francs per kilo, a profit of more than 700%. The next year, its stock price had risen to nearly 30 times what it was six years prior. Between 1890 and 1904, total Congo rubber earnings increased 96 times over, making it the most profitable colony in Africa.

Leopold became a madman, driven wild by the incoming wealth. He lusted for it. The only thing that could bite into his profits, however, was competition. For the moment, he possessed a sizable market share, but once cultivated rubber, which grows from a tree, would start to be produced in bulk, the price of rubber would drop. Such trees took much time and care before they could be harvested, so by the time the ones in Latin America and Asia matured, the rubber boom was 20 years old.

During that time, Leopold pushed his colony to produce as much rubber as possible, as quickly as possible. The kind that grew in the Congo was wild, not cultivated, so it was contained inside long, spongy vines that snaked through the trees over 100 feet high, then twined around the branches of up to half a dozen surrounding trees. Conveniently for the king, wild rubber required no cultivation, fertilizer or capital investment in expensive equipment. It only needed labor, and he had access to plenty of that.

White officers arrived at villages, carrying rifles and bearing the gold star on a blue background of the state flag. Upon sighting them, the Africans bolted. The soldiers ransacked the villages, taking all the chickens, grain, etc., from the houses. Next, they subdued any uncooperative natives, and grabbed the women and kept them as hostages until the chiefs brought back the required amount of rubber from the forest. Once the demands were met, the women were not yet released; they were sold back to the villages for a couple of goats each. If the men failed to supply the rubber, their wives were often killed and always raped.

In the rainforest, the extraction process was absolutely grueling. For much of the year, heavy tropical downpours turned the environment into hot, humid swamplands, which the rubber collectors were forced to trek through for hours or even days at a time. Then, upon finding a vine, they lightly tapped it and let the milky substance ooze into a bucket. If they wanted to drain the vine faster and collect more rubber, they could cut straight through it with their knives, which they often did because they were under such tremendous pressure from the Belgians. This, however, permanently killed the vine, so it was expressly forbidden and often punishable by death.

As the state officials returned again and again for more rubber, the reserves nearest to the village ran dry, forcing the men to travel deeper into the forest in search of fresh vines. They sometimes had to walk dozens of miles back to the village carrying heavy baskets of rubber. One alternative was for them to climb high up the trees, but this was hardly preferable as they risked death or injury by falling. It was not uncommon that one man discovered another lying on the ground with a broken back, moaning and writhing in pain.

After filling a container with rubber, a worker had to dry the substance so it would coagulate. The only way for him to do this was to smear it all over his arms, chest and thighs, and let it sit. “The first few times it is not without pain that the man pulls it off the hairy parts of his body,” wrote Officer Louis Chaltin in his journal in 1892. “The native doesn’t like making rubber. He must be compelled to do it.”

When the rubber collectors made it back home, exhausted, they presented what they had gathered to the colonial officers. The rubber was weighed, and if it did not fulfill the quota, even by a negligible amount, they killed or whipped the men at fault. The officer’s tool of choice was the chicotte, a whip of raw, sun-dried hippopotamus hide, cut into a long, sharp-edged corkscrew strip. It was typically applied to the victim’s bare buttocks, scarring them permanently. More than 25 blows could result in unconsciousness, and 100 were often fatal.

Baptist missionary John Harris recalled one scene. “Lined up are 40 emaciated sons of an African village, each carrying his little basket of rubber. The toll of rubber is weighed and accepted, but four baskets are short of the demand. The order is brutally short and sharp. Quickly the first defaulter is seized by four lusty ‘executioners,’ thrown on the bare ground, pinioned hands and feet, whilst a fifth steps forward carrying a long whip of twisted hippo hide. Swiftly and without cessation the whip falls, and the sharp corrugated edges cut deep into the flesh—on back, shoulders and buttocks. Blood spurts from a dozen places. In vain the victim twists in the grip of the executioners, and then the whip cuts other parts of the quivering body, and in the case of one of the four, upon the most sensitive part of the human frame.”

In an effort to disconnect themselves from the violence and demoralize the natives, the white officers often commanded the Africans to administer the punishments to each other, so they repeatedly struck their friends and family with the chicotte, enduring the sound of their wailing. In the most sickening cases, some of the men were forced to kill or rape their own mothers and sisters. In the face of this savagery, one can only remember Stanley's fateful commitment to help “civilization to overcome barbarism.”

King Leopold’s rule over the Congo was, without a doubt, the bloodiest episode of the Scramble for Africa. Between approximately 1880 and 1920, the territory’s population was cut in half, from 20 million to just 10 million, by murder, starvation, exhaustion, exposure, disease and a plummeting birth rate. Strictly speaking, it was not genocide; but it still rivals the Holocaust with its death toll, and yet those 10 million lost lives have been largely forgotten in the modern popular consciousness. Heart of Darkness is taught in English literature classes as a generalized anti-imperialist novel, not an accurate depiction of one specific place at one specific time. Joseph Conrad spent numerous months in the Congo, and his famous literary villain, Mr. Kurtz, is likely an amalgamation of several real colonial administrators.

In 1908, Leopold sold the Congo to the Belgian parliament, and then died the following year. Over the next few years, reports of abuse in the colony slowed to a trickle, though forced labor, dangerous working conditions and use of the chicotte continued for decades after Leopold’s death, killing tens of thousands. Black African troops were sent to fight in both World Wars, and laborers were shoved back into the rainforest to harvest rubber for trucks, jeeps and warplanes. Over 80% of the uranium in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs came from a single mine in the Congo.

The territory did not gain independence from Belgium until 1960, and even then it had to fight for it. The first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, stressed the need not just for political independence, but economic independence from Europe. The American empire began biting its nails, and within two months of Lumumba’s inauguration, the National Security Council authorized his assassination. He was dead that January, shot by some Belgians backed by the CIA, and his body was subsequently chopped up and dissolved in acid. The US picked Joseph Mobutu, then Chief of Staff of the Army and former colonial officer, to rule the Congo. After extensive grooming in Washington, he seized power in a military coup in 1965 and repressed the Congolese people for the next three decades, loyally permitting Western corporations to plunder the country’s resources all throughout.

Today, 73% of the Congo’s roughly 80 million inhabitants live in extreme poverty; the second worst Ebola outbreak in recorded history is spreading across the country; and armed groups are threatening regional stability. One of the richest countries in the world in terms of natural resources, the Congo is also the third poorest in Africa. Its natural resources are estimated to be worth $24 trillion, poising it to become the continent’s most developed nation and making the stamping out of any flicker of hope for an auspicious future by the CIA even more depressing.

Click here for part two: What Climate Activists Can Learn.

Any information in this article derived from no clear source was taken from King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa by Adam Hochschild.

Comments

Post a Comment